Understanding Fatigue: The Science Behind Persistent Fatigue

Jul 10

/

Dr Sula Windgassen

Fatigue is one of the most misunderstood symptoms for many people struggling. If you're living with the heavy, oppressive exhaustion that doesn't lift after sleep, you're not alone and you're certainly not imagining it.

Fatigue isn't just normal tiredness, it isn’t about needing more coffee or hitting the 8-hour sleep goals. This is about the complex physiological reality of chronic fatigue that impacts lots of people with conditions like CFS/ME, inflammatory bowel disease, post-viral syndromes and burnout. Despite what you may have been told, fatigue is not "all in your head" - it's a real, measurable physiological response with identifiable biomarkers and mechanisms.

In this blog, I’ll explore the research on what actually happens in your body when you experience chronic fatigue, why psychological and social factors matter (without dismissing the physical reality) and some first-step solutions that may help with your fatigue. Whether your fatigue started with illness, stress or seemingly out of nowhere, understanding the science can be beneficial in your journey with managing it.

Fatigue is not just extreme tiredness

As I write this, my eyes are drawn, my heart heavy and my head a sensation I can't describe. I know from all these subtle (and yet not really subtle) sensations I don't have much bandwidth left. I know this because of years of attending to the signalling of my body and cross-referencing with research. I know this because intellectually I can see just how much is going on in my life right now.

For some of you fatigue may be an inconvenient symptom that comes unexpectedly when there seems to be no good reason, passing eventually to let you plough on as you expect to be able to. For others, fatigue may be a permanent fixture that has made your world smaller, causing you much grief and sadness.

Let's be clear, when I'm talking about fatigue, I'm not talking about extreme tiredness. I'm talking about the heavy sunken feeling, that makes you feel like you're wearing a sandbag, so that movement feels immense and unrealistic, leaving your body reeling at the prospect. Fatigue is the exhaustion that doesn't clear after a good sleep. That sets in at inopportune times, making you feel separated from all the opportunities you might like to access in life. It is oppressive, confusing and scary.

Fatigue is not all in your head

There's been much research on fatigue. Fatigue in the context of chronic fatigue syndrome /myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME), in the context of inflammatory bowel disease, in the context of cancer recovery, burnout and more. There has been much controversy in the exploration of the psychosocial component of fatigue in the context of CFS/ME. Although I won't get into this controversy here, I believe the root of it is in the difficulty we have generally in knowing and understanding the closely interrelated nature of psychology and biology. Fatigue is real. It is immensely physiological. It is not depression under another name. But it is also influenced by our psychological experiences, particularly those specifically related to the experience of fatigue.

This week I've found my brain grind to a halt, my body sluggish, my mood lower. I wouldn't describe it yet as fatigue but it's on its way there. Is that 'all in my head'? Is it not valid or physical because some of what is contributing to it is a lot of uncontrollable stress and difficult emotion? I wouldn't say so. And neither would the research.

How psychological and social experiences create fatigue

While psychological and social experiences are not the only things that create or start fatigue – and for many are not the primary driver of fatigue – for everyone they do significantly factor in the maintenance and exacerbation of fatigue. Here's how.

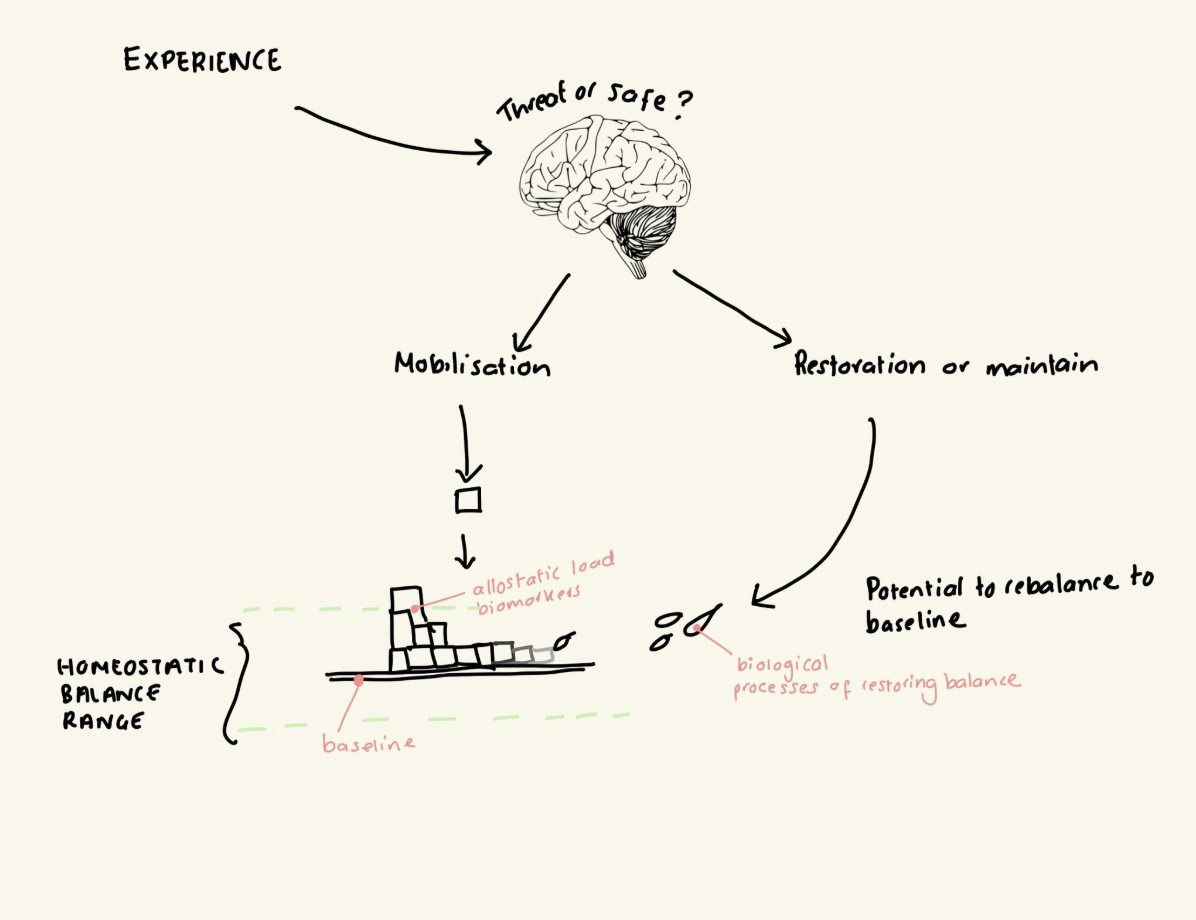

Psychological and social experiences can be broad, diverse, nuanced and multiple things at the same time. Let's take just one back-handed compliment. We can feel inferior, whilst proud, whilst self-conscious, whilst irritated. Our brain is doing multiple things to process and direct a response. We then have multiple processes happen in our brain to dictate and react to our own response and the social reaction to it. Just one interaction creates a plethora of processes in the brain (all of which are underpinned by physiological electrical and chemical reactions). As multifaceted as this all is, there is a general dichotomising that happens at the body level: is this a threat that we have resources to cope with, or is it a threat that potentially outweighs our capacity? Simplified further: safe or threat? If it's safe (or neutral), it is processed as benign or even restorative. If it is threatening, it is processed as something that will require resources.

This is where the concept 'allostatic load' comes in. Your body is constantly working to keep an equilibrium so that your body's systems can function as normal to restore, replenish and fight off infection. This homeostatic balance is designed to have flexibility so that you can deal with many stressors and demands. The issues come when a.) your body systems become depleted (e.g. infection, injury, trauma) and b.) when you have too many stressors and demands than you have capacity for.

In burnout, research demonstrates that neurophysiological processes change, as allostatic load increases and this is what contributes to burnout (1), which generally comes with physical symptoms like fatigue, recurrent infections and psychological symptoms like depressed mood, poor emotion regulation and heightened anxiety. 'Vital exhaustion' is a term used synonymously with burnout and refers to a specific state characterised by excessive fatigue, lack of energy, sleep issues and low morale. Studies seem to indicate that depending on the phase of burnout or exhaustion, different things might be happening under the surface biologically. For example, in earlier stages, the body may be increasing cortisol to allow you to mobilise, while later on, when the body's capacity to do so is inhibited is associated with hypocortisolism (a lack of cortisol) (2). This is one biomarker depicting physiological changes in response to stress, that can account for fatigue, but it is not all about cortisol levels (although they do have a big impact on your cardiovascular function, metabolic function, hormones and immune system function).

In fact, there is a specified variety of allostatic biomarkers, called the allostatic index. Specifically there are 14, which include inflammation indicators (like TNF-α, and IL-6), blood clotting factors that can increase the risk of heart disease or stroke, metabolic health measures like blood glucose levels, a specific stress related hormone (DHEA-S) and a range of cardiovascular health measures like heart rate variability and blood pressure (3). This reflects how numerous physiological processes change across key regulatory systems in your body in response to chronic cumulative stress (allostatic load). Burnout generally is associated with high allostatic biomarkers and specifically 'emotional' exhaustion measured by things like “I feel fatigued when I get up” and “I feel used up at the end of the day” are significantly associated with higher allostatic biomarkers (3).

To summarise, psychological stress and strain creates physiological demands on your body that can result in fatigue or exhaustion.

Biological drivers of fatigue

For many, fatigue did not start because of burnout, or psychological stress, but because of biological burden in the body. For example, in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), fatigue is a common secondary symptom even when the disease is managed. In recovery from cancer, people often experience high levels of fatigue that feel overwhelming. And in chronic fatigue syndrome or post viral fatigue, quite often there has been some sort of viral infection or other physiological ailment that coincided with onset of fatigue.

Fatigue is not “psychological”, in so much as getting repeated colds is not psychological. It is a symptom of physiological responses in the body to things that are inhibiting the body's natural processes to rebalance (i.e. reach homeostasis). That doesn't mean that both repeated colds and fatigue can't be massively affected by psychological experiences. It's important to recognise both when trying to work with fatigue to improve it.

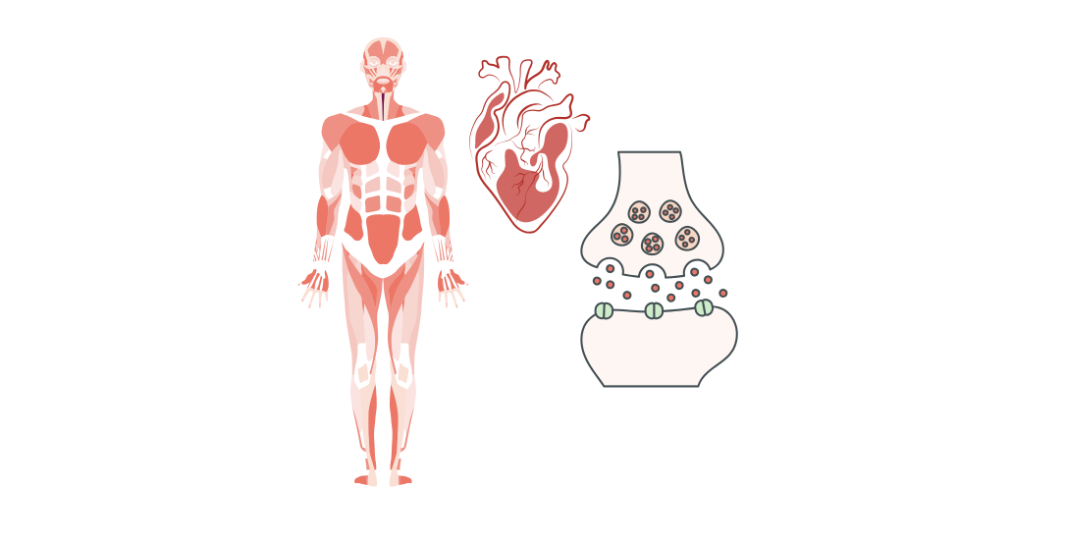

Research into fatigue in the context of CFS/ME, IBD and cancer, demonstrates that immune system processes play a significant role in fatigue (4–8). This makes sense also in the context of allostatic load. The immune system is a key regulatory system in the body that helps it to achieve homeostasis. When the immune system is impacted by injury or illness, this has a knock-on effect on other regulatory systems like our hormonal systems (neuroendocrine) and even our metabolic system. When these systems are impeded in their usual function there is more strain, less available cellular energy and therefore less available experienced energy. External factors other than stress will play a role on this delicate balance also. Exposure to pathogens, excessive heat, lack of access to sunlight or nutrients – all of this factors into the operation of the immune system and other regulatory systems.

When figuring out fatigue, we need to figure out what can help the operation of our regulatory systems. This will be highly personalised and yet, there are some common elements.

Solutions to start working on improving fatigue

As I mentioned previously, the approach to figuring out fatigue is personal and is dependent on each individual and their circumstances, but there are some common threads in the very basics.

Below are three initial, basic fatigue solutions:

1.) Good nutrition, tailored to your specific digestion style (e.g. slow transit) and dietary requirements. As a rule of thumb more variation of plants = better for the biome which is necessary for healthy functioning of other regulatory systems.

2.) Movement, tailored to your physical capacity. This is one that people struggle with most because it is not easy to work out. Reductive and restrictive protocols like spoon theory can mean people back off too much for fear of post-exertional malaise, which can mean that regulatory systems aren't rehabilitated adequately. That being said, pushing too hard means that the systems are depleted. It is a hard balance to strike and needs careful structuring and consideration, often with feedback because the anxiety and stress of the uncertainty and physical experience can add to the allostatic load.

3.) Working with your brain to reduce threat. This is almost too big for one single bullet point- but let me try. Fatigue is naturally threatening. It is threatening in symptomatology, in what it represents (“I can't do what I want”), in how it isolates, in how it dictates your sense of self. We don't want to adopt toxic positivity BS to pretend fatigue is ok. And yet, we need to make fatigue less of a threat. So we need to integrate in various elements to work on these various levels of threat. This might be reducing your body's automatic threat response to fatigue. It might be working on your relationship with yourself, so that you can still have compassion and acceptance for yourself when you can't do what you would like to do. It might be increasing your sense of safety in testing your parameters of capability with fatigue – crucial for retraining the brain's hypervigilant response to fatigue (9).

As ever there is so much more to say, but hopefully you've found this deep dive insightful.

TLDR?

Fatigue isn't just being tired - it's a real, measurable physiological response that feels heavy and doesn't improve with sleep.

Key points:

- It's not "all in your head" - fatigue has identifiable biomarkers and biological mechanisms

- Psychological stress creates real physical fatigue through allostatic load - when your body's stress response systems become overwhelmed and depleted

- Biological causes are equally valid - immune system dysfunction from illness, infection or chronic conditions directly causes fatigue by disrupting your body's regulatory systems

- Both psychological and biological factors matter - they work together to maintain and worsen fatigue

Three basic solutions to start with:

- Improved nutrition- a varied diet, with lots of plants, to support your microbiome and regulatory systems

- Careful movement - finding the balance between too little (fear of crashes) and too much (system depletion)

- Reduce threat perception - working with your brain to make fatigue feel less dangerous, improving self-compassion, and safely testing your limits

Bottom line: Fatigue is complex and real, and it’s important to address both the physical and psychological components without dismissing either.

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2025