'I Don't Know Why I Did That': Understanding Trauma Behaviour and Nervous System Responses

Aug 21

/

Dr. Sula Windgassen

Have you ever found yourself reacting in ways that feel completely unlike you during times of extreme stress? Perhaps you froze when you needed to act or snapped at someone you care about? Then later wondered, "I don't know why I did that - that's not like me at all."

If this sounds familiar, you're not alone. These seemingly puzzling behaviours aren't character flaws or personal failings - they're the result of profound biochemical and nervous system changes that occur when we're under extreme stress or have experienced trauma.

Understanding the science behind these automatic responses is crucial for healing, because self-criticism and blame can undermine even the most motivated therapeutic efforts. When we recognise that our brains and bodies are literally wired to respond in certain ways during threat, we can begin to approach ourselves with the compassion needed for genuine recovery.

“I don’t know why I did that”

In this blog, we’re exploring a little about how and why we have imperfect responses when under extreme stress or trauma. Here’s why it is important. In therapy, I can work with the most motivated, open and curious of people, but therapeutic efforts are almost sure to be undermined by the presence of high levels of self-criticism and blame, unless they are reduced to some degree. That tends to be a big feature of the work throughout therapy. But we need an initial in, to help update perspectives that firmly point the finger inwards. And I find that helping people understand what is happening in their brain and body really helps them to be a little gentler with themselves.

Your nervous system under trauma

Trauma is extreme stress, so when I’m describing the biology of this, you can think of it like a spectrum. Under the most extreme stress body responds in extreme ways, but his response can happen to different degrees depending on the degree of stress experienced.

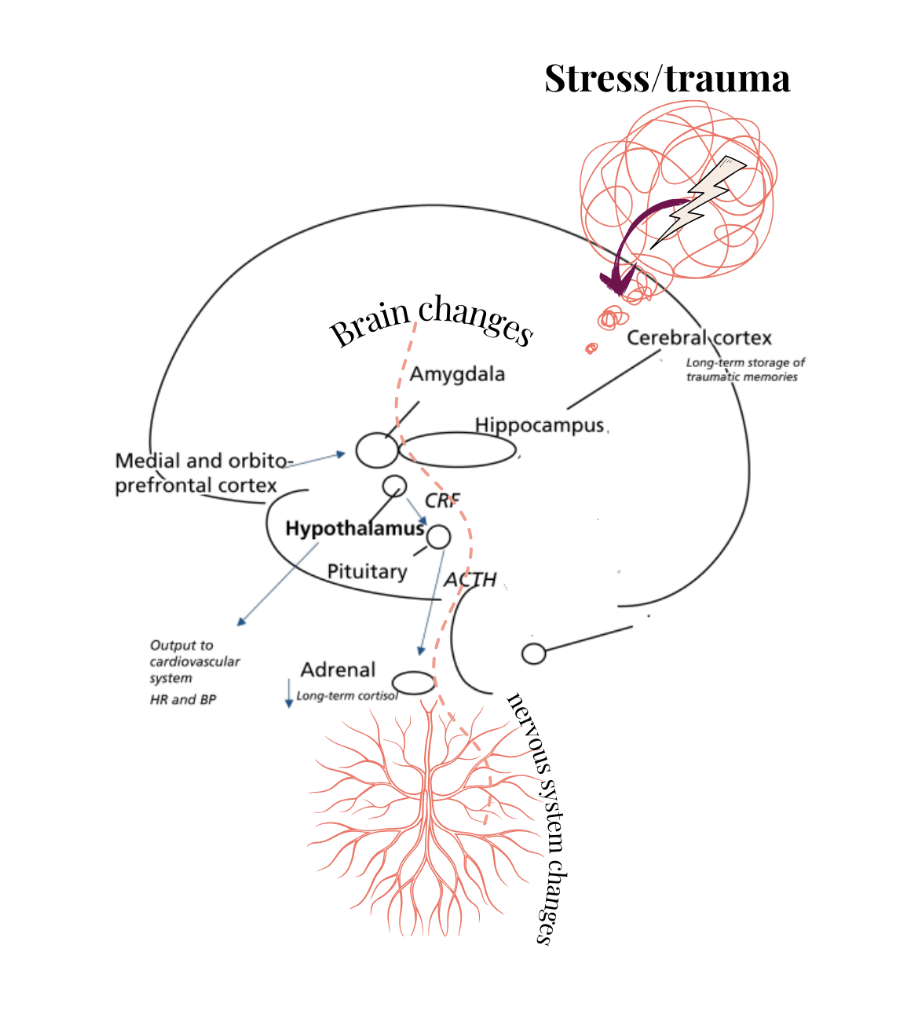

When you go through something extremely stressful and/or distressing, your brain is rapidly making calculations, ringing an alarm bell that is sounding out ‘threat, threat, threat’. Brain regions like your amygdala see high level of activation and account for this alarm bell.

As your brain is responding by prioritising emotions and generally dialling down access to rational thought, it is changing what is happening in your nervous system. The area of your brain in charge of orchestrating the stress response, the hypothalamus, is also firing off. Activity in the hypothalamus results in neurochemical changes. Specifically, the secretion of norepinephrine (that becomes adrenaline) and cortisol (1). The immediate intended effect of these hormones is to alert and mobilise (or immobilise i.e. freeze) to deal with the immediate threat.

This neurochemical changes are translated into changes in organ and muscle function by your autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system is the regulator of your involuntary bodily functions like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion and more. The influx of adrenaline and cortisol, mean that the subbranch of your autonomic nervous system, your sympathetic nervous system, accelerates activity. Restorative bodily processes are put on hold to prioritise activation related to immediate protection. The thing about this is, ironically, it often feels the opposite of safe. You can get tunnelled or blurry vision, palpitations, sharp pain, and intense agitation. You can feel less in control than it feels like you need to be.

Another subbranch of the nervous system, the somatic nervous system, is also processing things differently under extreme stress. The somatic system carries sensory information from your skin, muscles and joints to your central nervous system, where this information is processed to determine sensation. The somatic system is also how you voluntarily control your muscles. It is the somatic nervous system that is being recruited when you contemplate heaving yourself off the couch.

When in extreme stress, your somatic nervous system executes the bidding of the brain and autonomic nervous system (2). Without a conscious thought you may find yourself running, lashing out, flinching or freezing, as your muscles rigidly tense up preparing for impact or as a (largely) outdated evolutionarily instinct to play dead. Freezing can feel so alien to us with access to thinking brains, that can see how that won’t help much in the context of many of our stressors or threats, and yet, it is a physiologically ingrained go-to. I don’t mind sharing, I tend to have more of a default freeze rather than fight response and I have over the years come to consider this as a strength, giving me time to digest situations, figure things out and not act out impulsively. However, for lots of people, it can be a source of shame or increase a sense of powerlessness. When I worked in the NHS, many people that I worked with had been through traumatic experiences escaping war, car accidents and violence, and there was an intense self-blame in how they had responded. We spent much time on how automated this response is – your brain (coordinated with the body via the somatosensory nervous system) essentially puts you out of the driver’s seat.

That’s not me!

Just as your autonomic nervous system and brain are instructing your somatosensory system without your conscious, cognitive consent, neurochemical changes in the brain that stimulate the release of adrenaline are cortisol, also change brain processes that affect how you behave (1, 3, 4). You may have experienced a loss of appetite when you hear something upsetting, pushing your plate away. Or not being help but snap or raise your voice when feeling criticised or attacked in some way. Or stopping your usual routine for fear it will cause more symptoms. All of these are examples changed behaviour influenced by neurochemical change in the brain because of trauma or extreme stress. Specifically, secretion of something called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF).

This demonstrates how automated our processing and actions can become under extreme stress. We should not forget this has evolutionarily been adaptive and kept us alive – even if it does cause us problems in the present day with present day threats and stressors. We should also not forget that our imperfect actions under extreme stress are not character defects. We are organisms not always fully in charge of all our internal processes!

It is also important to recognise the role of biology when your find yourself in a stand-off with your brain/body. One part of you desperate to do or not do something, but your brain/body seemingly having different ideas. From trying to up pacing activities when you have fatigue, to making a call to the doctors when you’ve been dismissed many times before. You can get so frustrated at yourself. Why can’t you just do it?? Well hopefully this has gone someway to help you understand that there are very physical processes at play that are intended to protect you.

This is why I am rarely surprised and never frustrated when my clients tell me they didn’t do they home practice. Aside from the practicalities of life, quite often home practice poses a sense of threat. It is an activity that means turning towards and tackling face on difficult experiences. Of course the brain is going to be resistant! We simply work out how we can make it feel a little safer and more accessible or give the brain another ‘run up’ opportunity the following week.

Time to reflect

As ever, I finish writing feeling there is so much more to say. Perhaps now is a good time to reflect.

What action/inaction of yours do you often judge yourself for? Is there a possibility that this poses a threat to your system in some way? How could you be gentler?

TLDR

Trauma behaviour: Biochemistry and nervous system changes

The key insight: These responses aren't character defects - they're your body's evolutionarily hardwired attempts to protect you, even when they don't suit modern stressors.

Bottom line: Understanding that trauma responses are biological, not personal choices, is essential for self-compassion and healing. Your brain literally puts you "out of the driver's seat" during extreme stress - recognising this can transform self-criticism into self-understanding.

- Your brain prioritises survival over rational thinking - the amygdala sounds alarm bells whilst the prefrontal cortex goes offline

- Stress hormones flood your system - adrenaline and cortisol create fight, flight or freeze responses without your conscious consent

- Your nervous system takes control - automatic responses like freezing, snapping or avoiding happen before you can think

- Brain chemistry changes behaviour - neurochemical shifts affect appetite, mood and decision-making

The key insight: These responses aren't character defects - they're your body's evolutionarily hardwired attempts to protect you, even when they don't suit modern stressors.

Bottom line: Understanding that trauma responses are biological, not personal choices, is essential for self-compassion and healing. Your brain literally puts you "out of the driver's seat" during extreme stress - recognising this can transform self-criticism into self-understanding.

References:

1. Bremner JD. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006 Dec;8(4):445–61.

2. Kearney BE, Lanius RA. The brain-body disconnect: A somatic sensory basis for trauma-related disorders. Front Neurosci [Internet]. 2022 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Jul 13];16. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.1015749/full

3. Koob GF, Heinrichs SC, Pich EM, Menzaghi F, Baldwin H, Miczek K, et al. The Role of Corticotropin-Releasing Factor in Behavioural Responses to Stress. In: Ciba Foundation Symposium 172 - Corticotropin-Releasing Factor [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; [cited 2025 Jul 13]. p. 277–95. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470514368.ch14

4. Duque A, Cano-López I, Puig-Pérez S. Effects of psychological stress and cortisol on decision making and modulating factors: A systematic review. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2022;56(2):3889–920.

Free webinar

How your childhood changed your health

Body Mind Connect will be hosting an upcoming webinar that will explore the profound connection between childhood experiences and your health in adulthood, deep diving into how early stress and trauma create changes in both brain and body. Our founder, Dr. Sula Windgassen, will draw on both research and clinical experience, and guide you through understanding how your early experiences can influence your physical and emotional wellbeing.

Write your awesome label here.

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2025