What Happens to Your Brain When You're Traumatised? The Neuroscience of Trauma and Recovery

Aug 15

/

Dr. Sula Windgassen

Have you ever wondered why trauma symptoms feel so overwhelming and difficult to control? Or why your brain seems to react so intensely to certain triggers long after a traumatic experience has passed?

The answer lies in understanding what actually happens to your brain when you're traumatised. It is far from being "all in your head" - trauma creates real, measurable changes in brain structure and function that explain why you might experience flashbacks, hypervigilance, emotional numbness or difficulty concentrating.

In previous blogs, we’ve covered what trauma is and what it does to your body. In this blog, we'll explore the fascinating neuroscience behind trauma responses, examining how experiences of extreme stress physically alter key brain regions like the amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. We'll also look at how trauma rewires entire brain networks, affecting everything from threat detection to memory processing.

Most importantly, we'll discuss how understanding this can reduce shame around trauma symptoms and open pathways to healing. Because whilst trauma changes the brain, research shows that with the right approaches - for example, trauma-focused therapies like EMDR and CBT - these changes can be repaired, helping your brain become "unstuck" from past experiences.

Now perhaps you may be wondering what happens to your brain when you are traumatised?

Now perhaps you may be wondering what happens to your brain when you are traumatised?

What are trauma symptoms and why do they happen?

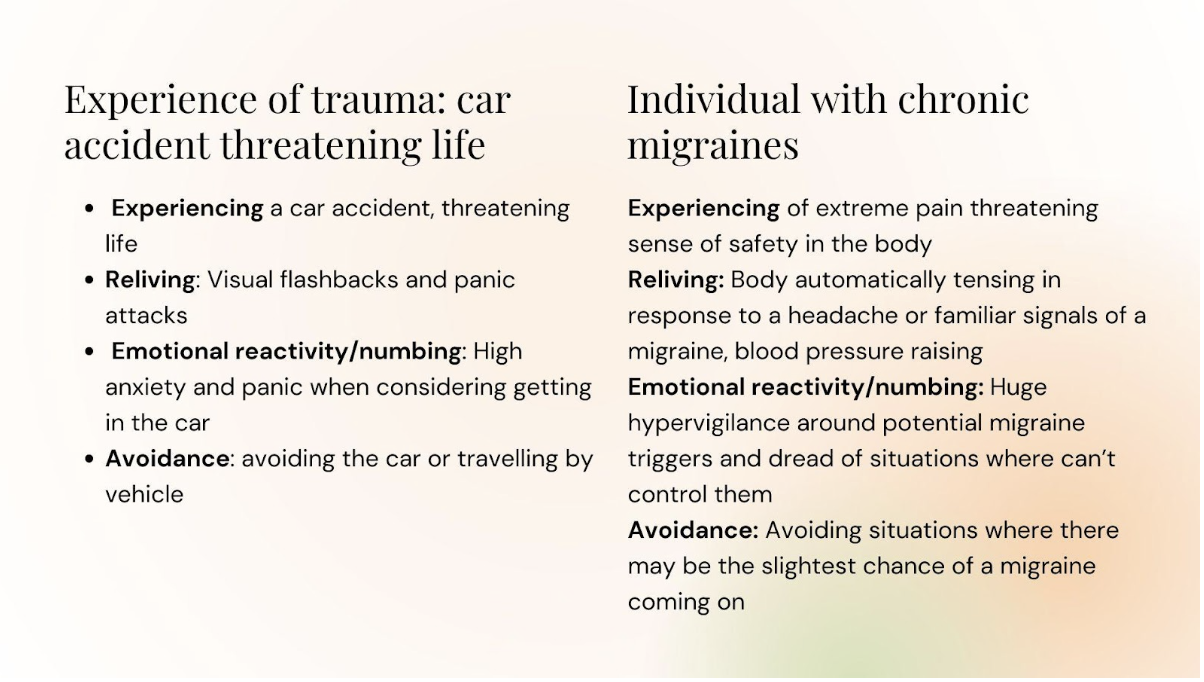

When I was doing my psychotherapy training, I remember starting work with my first post-traumatic stress disorder ‘case’. I had been simultaneously nervous and intrigued to work with someone who had PTSD. Trauma seemed such a big thing to tackle head on with a therapeutic protocol. It offered both hope and a challenge. As part of this training, I became experienced at spotting the key features of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD:

- An experience of trauma (defined as exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence)

- Reliving of that trauma (through nightmares, physical or somatic sensory experiences, visual or auditory flashbacks)

- Emotional reactivity or numbing/dissociation

- Avoidance – avoidance of emotions or of situations that may trigger reexperiencing

My first ‘PTSD case’ was a revelation to me. John* was a first line responder and had witnessed awful things. He was finding it hard to square his knowledge of the terrible things that could happen on his doorstep, with his everyday life. I loved working with John. He was not big on emotions and yet there was so much emotion in the trauma. I didn’t really know it but some of what I was doing in session with him, was coaxing him to acknowledge and be with that emotion. Yet when it came to the trauma reexperiencing part of our sessions, he became more stoic. His brain simply would not allow that emotion to come up. It was fascinating to me, in retrospect as I wrote my case report, to see how emotion could be coaxed out in safe discussion together, with apparent effects on symptoms outside of sessions, and yet when we came to the full-on trauma-processing element, that emotion would be vanquished.

Years later when I trained in EMDR a whole new way of understanding and working with this phenomenon opened up to me. When I’d learnt trauma-focussed cognitive behavioural therapy, I became thoroughly interested in the element of the therapy that involved explaining how trauma affects the brain. I noticed that just sharing these details with my patients with PTSD could shift something. The shame or powerlessness hung a little less heavy. An avenue of hope in changing the brain materialised where there had been nothing but dead ends. With the EMDR training, this understanding of the brain processes in trauma (and trauma processing) vastly developed. Admittedly through a lot of my own additional research, because it just all seemed so -and I’m sorry to use this word but- magical.

As I was doing this research I was recognising that trauma symptoms in PTSD can be seen in people who don’t have PTSD but have experienced trauma and extreme stress or adversity.

Let me give an example:

This similarity led me to believe that perhaps the brain processing that gets altered in the context of PTSD trauma, can also be altered to a different degree in other experiences of trauma or extreme stress and adversity. To understand if this is the case, I had to check my understanding of what happens in the brain in response to trauma and then compare.

What happens to the brain when you are traumatised?

When you are in the traumatic experience, your brain cannot process information like it would usually do. Processing becomes primal to keep you alive. And this means an area of the brain called the amygdala becomes highly active, overriding the part of the brain that is usually running things to keep you organised and rational (to an extent at least). This more ‘cognitive’ or intellectual and strategic region of the brain is called the prefrontal cortex. When it temporarily gets suppressed by the amygdala it means you can’t access decision making, ration and impulse control as you could in usual circumstances. The amygdala is sounding the alarm loud to send distress signals to your hypothalamus.

The hypothalamus, is the area of the brain that orchestrates your stress response (both short term and longer term chronic stress response). When the hypothalamus hears the amygdala sounding (so to speak) it quickly floods the body with hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, which creates a load of bodily changes including increasing your heart rate, blood pressure and heightening some senses whilst dampening others.

The traumatised brain gets stuck in a sense of danger

The extreme activation of the amygdala when traumatised or extremely stressed, can lead to it remaining more easily activated, so that you experience spikes of intense emotion, fear, tension or sense of needing to act repeatedly, or perhaps feel a heightened baseline sense of hypervigilance (1). Not only have brain imaging studies found that the amygdala can become more hyperactive after trauma, they have also shown that the amygdala can physically shrink in size (1). The significance of this is in research showing that reduced amygdala volume, corresponds with stronger fear and stress responses.

The changes in amygdala function and even structure tend to go along with a reduced ability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate the amygdala (2). It becomes less active, contributing to more challenges in regulating emotional responses and difficulties in decision making, with a sense of not being able to ‘sort out thoughts’ that is common in trauma and chronic stress.

As your brain becomes less able to moderate messages of threat, it also has difficulty contextualising trauma memories and ‘time stamping’ them so that they are identified as past events, rather than present threats. This distinction is crucial because it also determines how ready and able your amygdala (and the rest of your body) is to relax and recalibrate. If a memory can’t be fully processed as a past event, there is a sense that at any minute you might be back in that position of extreme threat or stress and so your body’s resources are taxed to keep you vigilant.

The reason your brain struggles to ‘time stamp’ these events as past events is because an area of your brain that is responsible for both long-term memory processing and emotional regulation, the hippocampus, has also been dysregulated by the experience of extreme stress (3). A meta-analysis (pooled data analysis of all studies conducted on the particular research question) found that the onset of PTSD was associated with a reduction in volume of the hippocampus (3).

If we can see these processes happening in extreme trauma in the context of PTSD, according to my hypothesis (that the brain processes can also be altered in response to trauma and extreme or chronic stress outside of PTSD), we should see something similar outside of PTSD diagnoses. Was I right?...

I sure was! A meta-analysis of 83 functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies exploring the link with adverse life experiences and changes in the brain, showed that such experiences were associated with more amygdala reactivity and reduced PFC control. Another meta- analysis showed that communication between the amygdala and hippocampus was changed in those who had experienced early-life adversity (4).

In short, threatening experiences- whether classified as trauma or not – have the capacity to change the structure and function of your brain.

The rewired brain networks after trauma and extreme stress

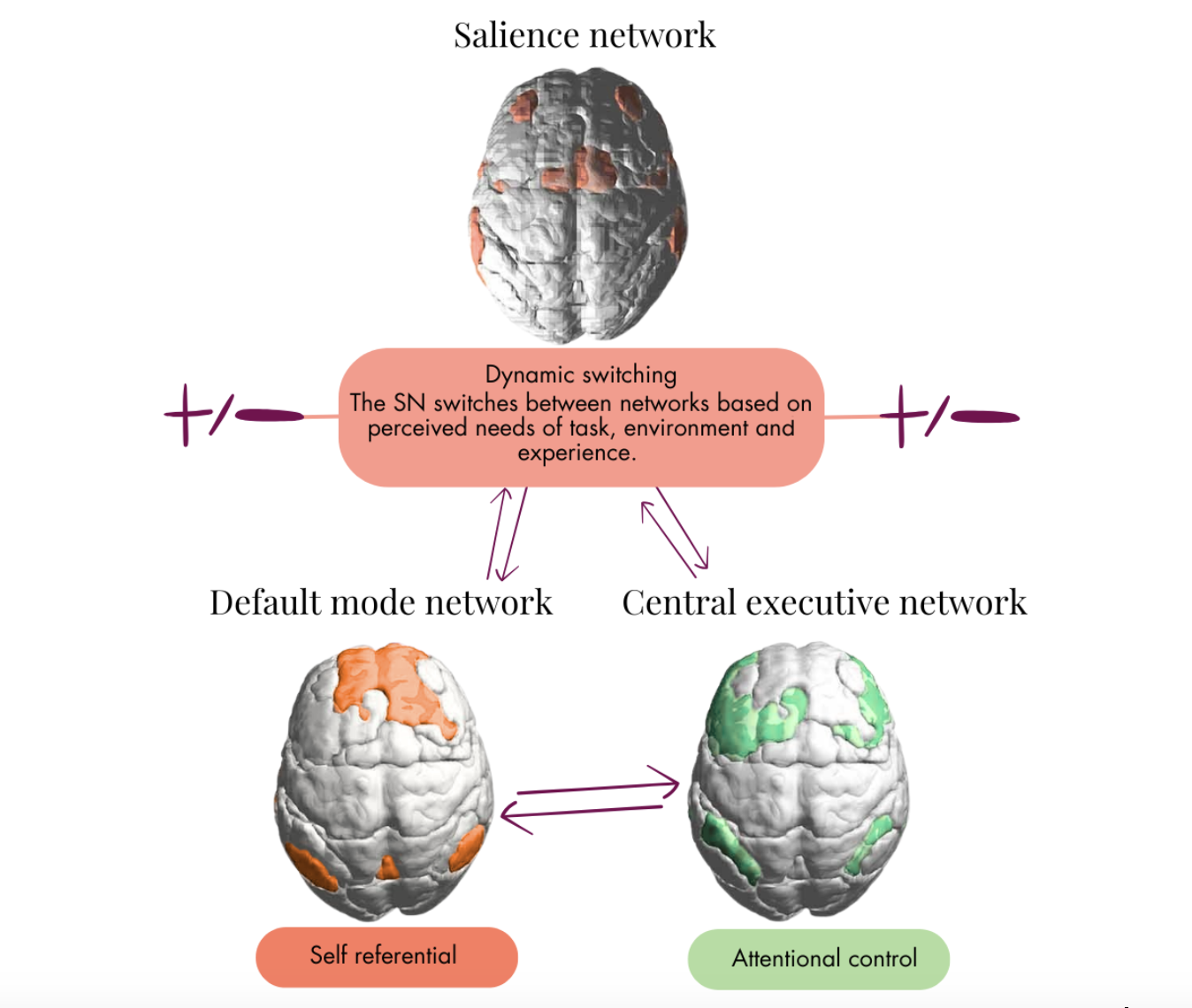

There are different networks in the brain that consist of brain regions that are separate from each other, but connected structurally and functionally. Structurally there are bundled nerve fibres connecting different areas of the brain. Functionally, these nerve fibre ‘super highways’ allow for coordinated neural activity in different areas of the brain. Different patterns of neural activity across different established brain networks correlate with different psychological experiences. For example, increased amygdala activation after trauma can cause increased activation in regions of key brain networks responsible for directing attention like the salience network. A more threatened amygdala, corresponds with a more alert salience network, which results in more sensory, emotional and cognitive hypervigilance to threat. This is why someone only has to say ‘hosp’ for your brain to predict ‘hospital’ and have a sinking feeling if you have experienced medical trauma for example.

There are three key brain networks changed from trauma and extreme stress:

- The Default Mode Network (DMN): a network of brain regions involved in thoughts related to the self, lifetime memories and thoughts of the future. After trauma, the DMN often shows reduced connectivity, which can manifest as feeling stuck in the past, or having lost your sense of self (5, 6).

- The Salience Network (SN): brain regions in the SN coordinate activity to work out what to pay attention to and what to disregard, playing a big role in threat detection. As seen with the amygdala which directly influences the SN, research shows an increased reactivity in the SN, resulting in heightened threat detecting and difficulty relaxing (5, 6).

- The Central Executive Network (CEN): this group of brain structures are responsible for higher-order cognitive functions like problem-solving, planning and decision making. The CEN coordinates to help focus, regulate impulses and emotions. This is the network where the prefrontal cortex resides. As considered earlier, trauma and extreme stress can mean there is a decreased connectivity and activity in the PFC and the broader CEN, often being overridden by the SN (5, 6). This results in difficulties concentrating and regulating emotion.

We’ll explore these networks more in upcoming instalments, so be sure to subscribe to the newsletter if you haven’t already.

How your brain can become "unstuck" after trauma

Hopefully in recognising that the brain is physically affected by psychological experiences, you can garner a little compassion for yourself when you come up against difficulties that may be very likely a result of these brain changes. Even if you don’t consider yourself to have had trauma, recognising there is a continuum. In brain imaging studies it presents degree of activation (or lack of activation), rather than a brain region being on or off. That means that where your brain is calculating threat in some ways, similar patterns of firing may be happening like the one described. So demanding you ‘think better’ or shut off feelings, can be rather unfair, giving the patterns of electrical activity that are being triggered automatically.

Now, all that being said… we are not haplessly determined by electrical activity in the brain. We can work with our default biological responses to shift things, if we have the right guidance, knowledge and/or support. Indeed, research has shown that trauma therapies like trauma-focussed CBT and EMDR can physically change not only how the brain processes (e.g. reduced activation in the amygdala and improved ability of the CEN to regulate reactivity) (7, 8) but can also physically change the size of brain regions. In a fascinating study looking at what effect EMDR versus exposure had on the brains of participants with PTSD, researchers found that the size of the amygdala actually increased after EMDR (9).

Now I hear you, that might sound counterintuitive – but here's why it might increase, and it probably is a good thing, representative of healing. The volume may increase because more after EMDR because complex connections are being formed, with increased glial cells (that support neuronal activity), allowing for more nuanced processing of emotions that allow for more comprehensive integration of the distressing experiences.

Although not everyone needs specialised trauma therapy, what this does go to show is that there is plenty of scope for updating the brain and helping it get ‘unstuck’. If you’re curious about a relatively simple (and evidence-based) practice you might use to help your brain do just this, you may find the booklet linked here helpful. As ever, always more support available to have questions answered and get tailored feedback, in the Body Mind Connect community.

TLDR

What trauma does to your brain:

- Amygdala becomes hyperactive - creating intense fear responses and hypervigilance

- Prefrontal cortex gets suppressed - making it harder to think rationally and regulate emotions

- Hippocampus struggles with memory processing - causing memories to feel like present threats rather than past events

- Brain networks get rewired - affecting attention, self-awareness, and decision-making

The result: Your brain gets "stuck" in survival mode, constantly scanning for danger even when you're safe.

The good news: These brain changes aren't permanent. Evidence-based therapies like EMDR and trauma-focused CBT can physically restore brain function and help you heal. Understanding the neuroscience behind your symptoms can reduce self-blame and open pathways to recovery.

Bottom line: Trauma symptoms aren't a personal failing - they're your brain's natural response to extreme stress, and with the right support, your brain can learn to feel safe again.

References:

1. Henigsberg N, Kalember P, Petrović ZK, Šečić A. Neuroimaging research in posttraumatic stress disorder – Focus on amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 2;90:37–42.

2. Wolf RC, Herringa RJ. Prefrontal–Amygdala Dysregulation to Threat in Pediatric Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 Feb;41(3):822–31.

3. Del Casale A, Ferracuti S, Barbetti AS, Bargagna P, Zega P, Iannuccelli A, et al. Grey Matter Volume Reductions of the Left Hippocampus and Amygdala in PTSD: A Coordinate-Based Meta-Analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies. Neuropsychobiology. 2022 Feb 14;81(4):257–64.

4. Kraaijenvanger EJ, Banaschewski T, Eickhoff SB, Holz NE. A coordinate-based meta-analysis of human amygdala connectivity alterations related to early life adversities. Sci Rep. 2023 Oct 2;13(1):16541.

5. Schimmelpfennig J, Topczewski J, Zajkowski W, Jankowiak-Siuda K. The role of the salience network in cognitive and affective deficits. Front Hum Neurosci [Internet]. 2023 Mar 20 [cited 2025 Jul 11];17. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1133367/full

6. Hosseini-Kamkar N, Varvani Farahani M, Nikolic M, Stewart K, Goldsmith S, Soltaninejad M, et al. Adverse Life Experiences and Brain Function: A Meta-Analysis of Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. JAMA Network Open. 2023 Nov 1;6(11):e2340018.

7. Malejko K, Abler B, Plener PL, Straub J. Neural Correlates of Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2017 May 19 [cited 2025 Jul 11];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00085/full

8. Rousseau PF, El Khoury-Malhame M, Reynaud E, Zendjidjian X, Samuelian JC, Khalfa S. Neurobiological correlates of EMDR therapy effect in PTSD. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2019 May 1;3(2):103–11.

9. Laugharne J, Kullack C, Lee CW, McGuire T, Brockman S, Drummond PD, et al. Amygdala Volumetric Change Following Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. JNP. 2016 Oct;28(4):312–8.

Free webinar

How your childhood changed your health

Body Mind Connect will be hosting an upcoming webinar that will explore the profound connection between childhood experiences and your health in adulthood, deep diving into how early stress and trauma create changes in both brain and body. Our founder, Dr. Sula Windgassen, will draw on both research and clinical experience, and guide you through understanding how your early experiences can influence your physical and emotional wellbeing.

Write your awesome label here.

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2025