How Trauma Changes Physical Sensations in Your Body

Aug 26

/

Dr. Sula Windgassen

Have you ever wondered why physical sensations feel different after experiencing trauma or chronic stress? Why a gentle touch might feel overwhelming, or why you sometimes feel disconnected from your own body? The answer lies in how extreme stress fundamentally changes your brain's sensory processing systems.

Research reveals that trauma doesn't just affect your emotions and thoughts - it literally rewires how your brain interprets physical sensations. From the vestibular system that controls your sense of balance to the regions responsible for detecting internal bodily signals, trauma creates a cascade of changes that can leave you feeling unsafe in your own body.

In this deep dive, we'll explore how interoception, sensation and trauma or extreme stress are all interlinked, and the fascinating neuroscience behind these changes.

“I feel like I'm back there - help”

I'm writing fresh off reflecting about a few courses of therapy I delivered, which focussed on helping the brain recognise that things in the present were very different from how they'd been in the past. Specifically, these courses of therapy helped the brain differentiate present physical experiences (including pain, bladder symptoms and autonomic hyperarousal) from the previous contexts that made these sensations so overwhelmingly threatening.

This is not new work to me. It is my chosen area of specialism and yet, it still feels surreal, when we see that helping the brain update in this way, physically changes symptoms – even getting rid of them entirely.

So, today we'll consider how your sensory experiences are changed after trauma or extreme stress and why this also may make you feel disconnected from your body. As ever I'll include some resources that may help you, but I should remind you also that theBody Mind Connect membership helps with exactly these processes.

Extreme stress changes how you physically feel

In previous deep dives, I described the different brain networks that are affected by extreme stress and trauma. Within these different networks are brain regions that are responsible for processing, creating and integrating sensory experiences like touch, a sense of balance, tightness, pressure or posture. Research shows that foundational sensory systems, are disrupted when you experience trauma.

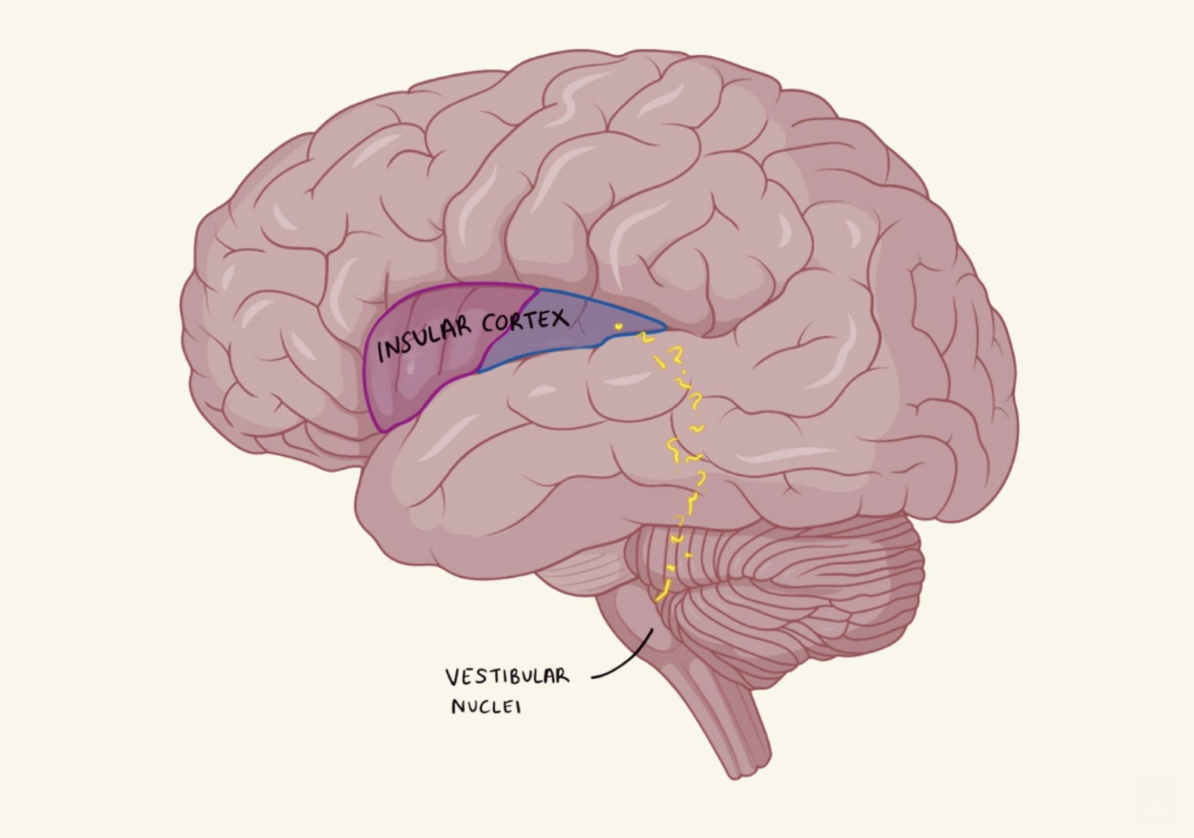

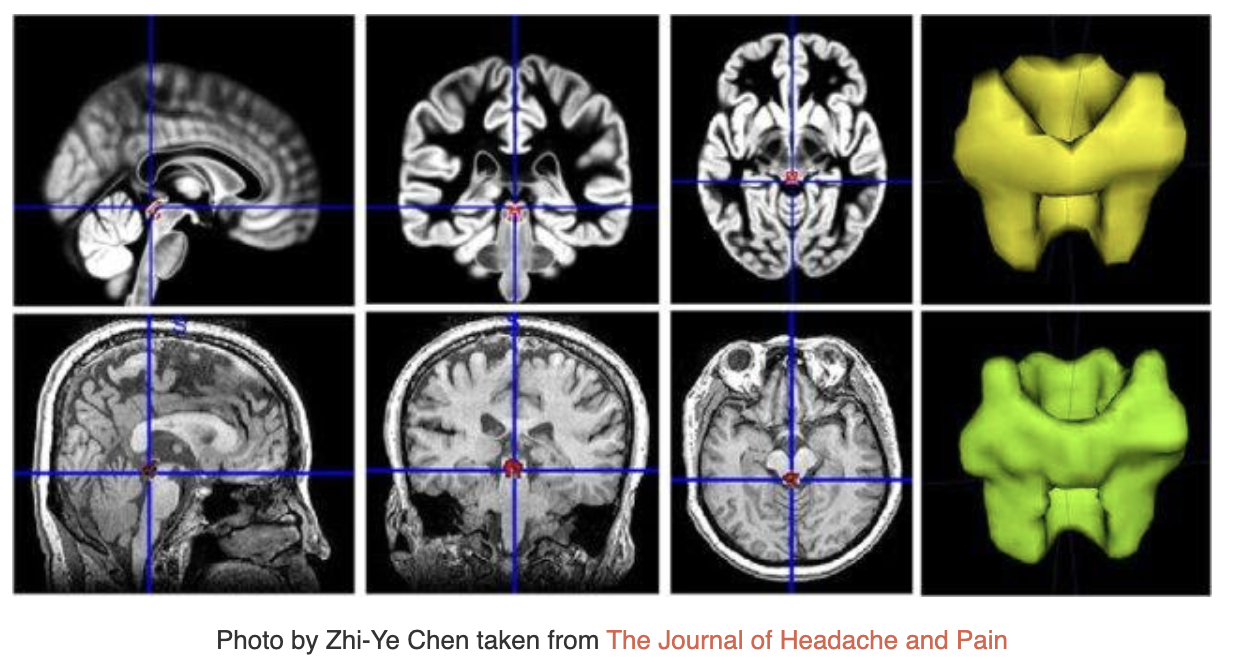

The vestibular system is the system that helps you have a sense of balance, recognise when you are in motion versus still and your spatial orientation. Brain imaging research shows that in PTSD, the vestibular nuclei (a specific brain region in the vestibular system) has reduced connectivity with another brain region, the posterior insula (4). The posterior insula is the main region of the brain that is responsible for you being able to detect your internal bodily state (interoception/interoceptive processing). For example, recognising an increased heart rate, hunger or gut feelings. When the vestibular nuclei and the posterior insula are having connectivity issues, the brain will have difficulties correctly appraising and contextualising physical symptoms you are experiencing. Essentially it can create a misinterpretation of bodily sensations that is therefore experienced more threateningly, creating a snowball effect of chronic hypervigilance to internal bodily sensations and potentially external situations that feel consequently more overwhelming.

The poor vestibular nuclei also appears to have difficulties communicating with 'higher order' brain regions- the brain regions that are involved with your conscious thought and active means of making sense of things (areas of the brain in the central executive network). Studies have shown that the area of the brain that is responsible for creating an embodied sense of self, so that you know you are here right now, in your body and separate from the outside world, (temporoparietal junction) has a weak communication with the vestibular nuclei in the dissociative PTSD subtype (1,4). This is associated with feeling detached from your own body, or as though you are an outside observer of your life.

These studies were conducted in the context of PTSD, where there has been extreme stress (trauma) resulting in a range of physical and emotional changes. Therefore, the findings are not necessarily applicable to those without PTSD – and yet – they still tell us something valuable. We can see how brain regions communicate with each other to impact physical experiences and also inform a sense of self existing in the world and how these processes change under particular conditions (extreme stress). So it follows that similar but less extreme conditions, can result in similar but perhaps less extreme changes to processing. Research supports the premise that high degree of stress outside of PTSD results in changes to processing that resemble changes seen in PTSD (1,5).

The changes in these brain regions can explain the 'shutting down' or 'numbing out' response of the nervous system (including the autonomic nervous system and somatic nervous system) that can lead to emotional disengagement, dissociative experiences and even not feeling pain.

Threat-focussed sensory processing

Just as likely and not mutually-exclusive, is the lowering of the threshold for detecting sensory input, meaning that smaller levels of physical sensation can lead to larger experiences of pain and discomfort (1,6,7). There are many precise mechanisms of this that span changes in neurochemistry, nerve activity and communication between different brain regions. The frustration for patients experiencing this changed threshold is that their pain is very real, and yet somehow, because psychological processes have had an impact on their brain meaning it has shifted how it processes – it can feel like pain or sensation is 'all in your head' and/or 'your fault'. Let's be clear – heightened sensation after trauma or chronic stress is neither of those things. It is being physiologically mediated, but just in a different way to how it once was. This is because your body is hedging its bets that you are in danger so shifting the way it produces sensation so you can easily be alarmed to danger.

At the bottom of your brain are what are thought of to be the most foundational and primitive brain structures, the brainstem and midbrain. The ones that could keep you alive even if the top parts of your brain (the parts that allow you to consciously think, feel, act and respond) were out of action. These areas integrate sensory input and coordinate survival responses before the information reaches your higher order conscious brain regions. High degrees of stress and trauma can disrupt these regions too, which can mean that your muscles automatically tense, your autonomic nervous system automatically primed for action and other regulatory systems primed for arousal in case of threat without a conscious thought (1,8). So if I haven't convinced you enough already – that means it is not you and your thoughts that are converting sensory experiences, but a baseline shift in how your brain is processing before you've even had a conscious thought. Now – the good thing about this is that it just because you aren't causing it with your thoughts, it doesn't mean how you think, what you do and how you work with your brain and body, can't make a big difference to the processing of these brain structures.

Physically transported back to fear

One thing that is common both in PTSD and in the people I work with, who are dealing with highly distressing physical symptoms, is the automatic transportation into a state of fear or panic from a physical sensation. In PTSD, for example, someone who was in a car accident, propelled through the window, may feel a sudden surge of dread and panic when they feel the taxi they are in breaking. The sensation has matched up to the same one experienced in the past – albeit to a different extent and that has brought up all of the related emotion. The same thing happens for those experiencing disruptive sensations due to health issues. They might feel a slight twinge, only to then suddenly feel sure that they are going to get a full-on flare up and be out of action for days. This is likely due to the same brain mechanisms.

An area of the midbrain, called the periaqueductal gray (PAG), integrates sensory information with emotion. This determines if something is safe or threatening. The sensory experiences and threatening contexts of them, can mean that the PAG easily matches hints of the sensation with the same emotion, so that you are sufficiently alerted to the threat (9,10). The difficulty in this process is that what this quite often means in practice, is that this brain activity creates a loop, meaning you feel stuck in active symptoms or fear of symptoms.

An area of the midbrain, called the periaqueductal gray (PAG), integrates sensory information with emotion. This determines if something is safe or threatening. The sensory experiences and threatening contexts of them, can mean that the PAG easily matches hints of the sensation with the same emotion, so that you are sufficiently alerted to the threat (9,10). The difficulty in this process is that what this quite often means in practice, is that this brain activity creates a loop, meaning you feel stuck in active symptoms or fear of symptoms.

I don't feel like me

Over the last year or two, I have had 100s of introductory calls with people seeking therapy, generally for support with trauma, chronic stress or health issues or a combination of all three. The most common aim for therapy is to 'feel like myself again'. We have just touched the smallest corner of changes happening in the brain responsible for changes at the most foundational level- your sensory experiences. We've also seen how the temporoparietal junction, the area of the brain that helps you feel present and connected with your body, has reduced communication with areas of your brain that physically help you to sense where you are and what is happening to your body. It therefore makes complete sense that you might feel less connected to yourself when you've been through trauma, repeated health issues or ongoing stress.

Creating a sense of safety

This research (and much more) illustrates why to feel connected to yourself and help yourself feel safe again, it is so important to work directly with your body and brain. Thinking and updating how your brain is conceptualising things from top-down (conscious, thinking brain down to unconscious sensing brain and nervous system) is one part of the equation for sure, but physically and emotionally feeling is another huge component. This is where people are increasingly turning to somatic therapies, which can be hugely transformative.

It's important to recognise that in the brain (and therefore the nervous system) there is an integration problem. There's reduced or changed connectivity. What we need is to improve communication between these brain regions and systems. Therefore, in my clinical practice and in the Body Mind Connect community, I facilitate exploration, practices and strategies that are focussed on improving this integration. Some of that is experiential work and some of that is cognitive. As you work on both, your brain becomes better able to integrate again for you, in a safer and more regulated way.

Time to reflect

To give you an idea of what this looks like, I've included two different exercises linked below. One that works more top down on updating your brain, and one that works more 'bottom up' to help your body feel safer. Click the links to access these.

TLDR

Trauma changes how your body physically feels

Your brain's sensory processing gets disrupted - the vestibular system and posterior insula lose communication, making you misinterpret bodily sensations as threatening

Physical sensations become danger signals - your periaqueductal gray matches current sensations with past threatening experiences, creating automatic fear responses

You feel disconnected from yourself - reduced connectivity between brain regions responsible for sensing your body and feeling present leaves you feeling "not like me"

Your nervous system stays on high alert - primitive brain structures automatically tense muscles and prime your system for threat before conscious thought kicks in

The key insight: Heightened pain sensitivity and disconnection after trauma aren't "all in your head" or your fault - they're real physiological changes in how your brain processes sensations to keep you safe.

Bottom line: Feeling transported back to fear by physical sensations is your brain's protective mechanism gone into overdrive. Healing requires both top-down cognitive work and bottom-up body practices to help your brain integrate and feel safe again.

References:

(1) Kearney BE, Lanius RA. The brain-body disconnect: A somatic sensory basis for trauma-related disorders. Front Neurosci [Internet]. 2022 Nov 21 [cited 2025 Jul 13];16. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.1015749/full

(2) Harricharan S, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA. How Processing of Sensory Information From the Internal and External Worlds Shape the Perception and Engagement With the World in the Aftermath of Trauma: Implications for PTSD. Front Neurosci [Internet]. 2021 Apr 16 [cited 2025 Jul 13];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.625490/full

(3) Lenart-Bugla M, Szcześniak D, Bugla B, Kowalski K, Niwa S, Rymaszewska J, et al. The association between allostatic load and brain: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022 Nov 1;145:105917.

(4) Crettaz B, Marziniak M, Willeke P, Young P, Hellhammer D, Stumpf A, et al. Stress-Induced Allodynia – Evidence of Increased Pain Sensitivity in Healthy Humans and Patients with Chronic Pain after Experimentally Induced Psychosocial Stress. PLOS ONE. 2013 Aug 7;8(8):e69460.

(5) Rivat C, Becker C, Blugeot A, Zeau B, Mauborgne A, Pohl M, et al. Chronic stress induces transient spinal neuroinflammation, triggering sensory hypersensitivity and long-lasting anxiety-induced hyperalgesia. PAIN. 2010 Aug 1;150(2):358–68.

(6) Myers B, Scheimann JR, Franco-Villanueva A, Herman JP. Ascending mechanisms of stress integration: Implications for brainstem regulation of neuroendocrine and behavioral stress responses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2017 Mar 1;74:366–75.

(7) Hohenschurz-Schmidt DJ, Calcagnini G, Dipasquale O, Jackson JB, Medina S, O'Daly O, et al. Linking Pain Sensation to the Autonomic Nervous System: The Role of the Anterior Cingulate and Periaqueductal Gray Resting-State Networks. Front Neurosci [Internet]. 2020 Feb 27 [cited 2025 Jul 13];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2020.00147/full

(8) Mills EP, Keay KA, Henderson LA. Brainstem Pain-Modulation Circuitry and Its Plasticity in Neuropathic Pain: Insights From Human Brain Imaging Investigations. Front Pain Res [Internet]. 2021 Jul 30 [cited 2025 Jul 13];2. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pain-research/articles/10.3389/fpain.2021.705345/full

Free webinar

How your childhood changed your health

Body Mind Connect will be hosting an upcoming webinar that will explore the profound connection between childhood experiences and your health in adulthood, deep diving into how early stress and trauma create changes in both brain and body. Our founder, Dr. Sula Windgassen, will draw on both research and clinical experience, and guide you through understanding how your early experiences can influence your physical and emotional wellbeing.

Write your awesome label here.

About Dr Sula Windgassen, PhD

Dr Sula is a Health Psychologist, Cognitive Behavioural Therapist, Eye Movement Desensitisation & Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapist and Mindfulness Teacher. Trained at King's College London & publishing papers on the use of psychology to improve health and whole-person wellbeing.

Featured links

Copyright © 2026